Margo Williams Interview. A Serious Case of Spontaneous Combustion. Part 1.

Summary Content Part 1: Interview in Under a Minute | Bomb-Damaged London | Chemical Genius | Into Africa | The Laboratory | White People are Weirder Than Black People | The Margarine Life | A Penguin is My Baby |

Part 2. Sweet Thursday in a Cannery Town

Part 3. Only One Hotel in Hellsville

Interview in Under a Minute

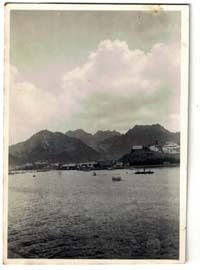

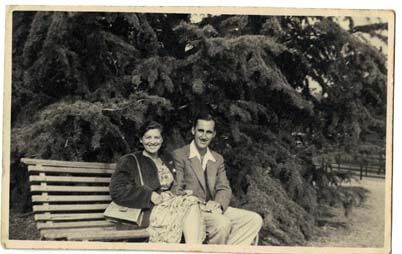

Ghost-hunter Margo Williams and husband Walter escaped a war-cratered city of London and found themselves at a wooden town whaling station in the Namibian desert coast in Africa.

Out of the darkness of late night she walked into a bar in a desert-shack hotel heaving with English-hating Afrikaners. The air stank of cigarettes, alcohol, vomit and whale-blood.

Genius explosives expert Walter Williams summoned to solve the serious case of spontaneous combustion - exploding fish.

The Williams' journey to that moment offered a portrait of the couple, good times and bad. To Hellsville, on planet earth where “normal” is as relative as weird.

How and Why Margo Williams Travelled to Africa

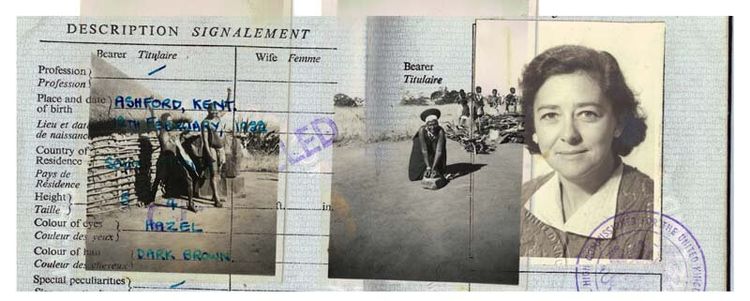

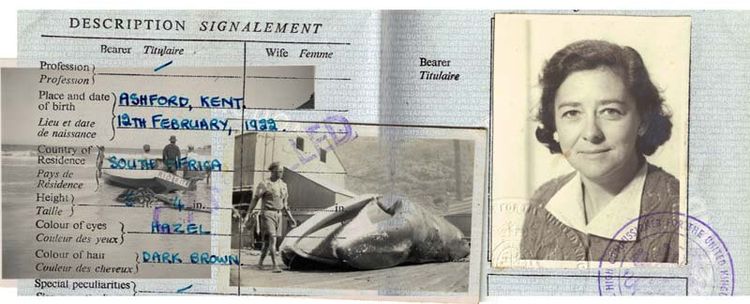

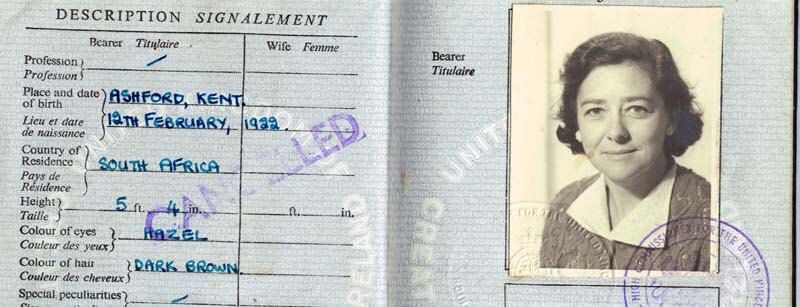

"We sailed on the Capetown Castle," said Margo Williams. "A ship making its first passenger run since commandeered as a troop ship during the war. Every birth taken by people emigrating to South Africa and Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe).

It was the first time I had ever left the shores of England and despite my nervousness over leaving friends and family I felt excited.

The London I left behind in January 1947 was not such a mess as it had been; piles of rubble still here and there and a few craters but Londoners had worked hard to repair the damage and pulled down the dangerous skeleton structures of bombed-out buildings.

New prefabricated homes were springing up on the bomb sites. They looked beautiful, little bungalows made of great sheets of asbestos bolted together. No one knew of the material's dangers, then. The bungalows were basic, not luxurious, two bedrooms and a bathroom. I wanted one. We had never had our own home together. So many people were homeless; everyone wanted one of these “prefabs”.

But London was a smashed, hungry city of horror-and-loss memories.

It started with incendiary bombs, ignited fires where they landed and spread, so during air raids people had to go outside, out of the shelters to firefight.

“Doodle-bug” bombs destroyed whole street communities, their factories and office blocks. V2 rockets followed, city-maiming munitions. Even in the aftermath of wartime we all still stared at a carcass city, everyone half-starved hungry from rationed food.

It hadn't been a difficult decision to leave, especially for an offer too good to refuse.

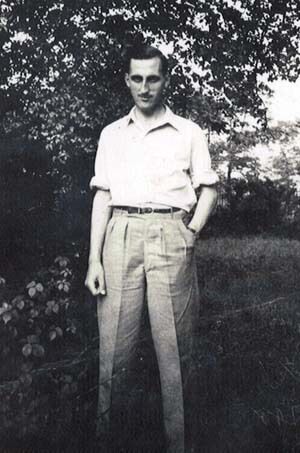

Walter Williams. Barefoot Genius

Walter hadn't gone to fight on the front during the war because he was a talented chemical engineer. His company boss argued with the War Office that his expertise was of vital importance to the war effort, and must be allowed to continue working in the munitions factory.

Chemical development work on explosives, very hush hush, making better bombs to drop on Germany.

Walter also was obsessed with fish, and when one day at the end of the war a man visited the company to head-hunt a chemical engineer to set up a fish oil refinery in South Africa, he spotted Walter and made him an offer – money, sunshine and as much fish to experiment on as he wanted. Walter was hooked.

I remember when he returned from the Dorchester where the boss had taken him to dinner. I could tell he was excited, so much so, he jigged around the room in that ill-fitting dinner jacket and dickie-bow. “I've got it! I've got it!” His expression I will never forget.

Walter Williams Accepted the job in Africa.

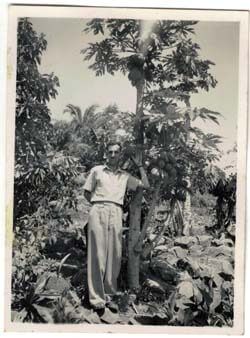

Into Africa

A fantastic job. A factory to be built and machinery installed and people to be trained in refining fish oils and fish meal. Walter was given his own laboratory and the first job was to oversee the construction of a large deodorising plant.

Bags packed, we headed for the tropical lands of Africa, first-class and all fares paid. As the sea miles slipped past and the sunshine grew hotter each day I felt the tension from the war slipping away.

Walter looked relaxed too on the journey. After the dust and terrible claustrophobic darkness of the air-raid shelters the smell of the sea filled my senses as the strange cloud-banks I saw from time to time in the distance caught my imagination.

How old were you when you travelled to Africa?

'Twenty-five,' answered Margo.

'My wishes were granted. We were provided with a works bungalow near the refinery. There were five others for the executives and factory managers, who were Afrikaaners Some spoke English. Walter was busy every day at the factory and so I was left to amuse myself and find my feet in this strange new world.

The factory was only a mile distant from the British Naval base of Simon's Town. A busy place and I soon found friends among the wives and built a routine of tennis and swimming. I had never swum before and discovered such a love for the waters I could scarcely be pulled away from the beach where I spent hours with the other girls playing water ballet.

The Margarine Life in Simon's Town

Walter expected his breakfast cooked every morning at eight-thirty and then I had the day to myself until he returned in the evening when supper had to be on the table.

Most evening were spent reading or listening to the radio. Sometimes Walter talked about work, often to complain about someone or other who worked for him. He was a genius and sometimes forgot how the rest of us aren't so quick to pick things up.

There were parties but we never attended. Not a big socialiser Walter didn't approve of parties unless it was a formal business do where he could talk fish with other engineers. Often he was called away to the city and then I got an invite to some officers' wives parties at the naval base.

On one occasion he showed me his work in the refinery, he felt very excited about a new margarine refinement process. I was escorted around the factory, shown the shiny machinery. Walter pointed to a coal-black substance oozing through the machine. I asked what it was.

“Margarine,” replied Walter, proudly.

I said it didn't look much like margarine and he wouldn't get me eating any.

Walter looked hurt and sounded cross. “It hasn't been bleached or deodorised yet.”

I also learned that day how Walter's factory mixed fish into bread, which seemed to me a bit disgusting. "Makes the bread more nutritious," he continued in excited scientist-style. “Everyone has it. It's in all the bread," he added, then deflated disappointed in my response. "Yes, it smells bad at first until it is deodorised. People wouldn't eat it otherwise.”

White People Are Weirder than Black People

Walter didn't ever take me again to the factory. And I wasn't upset by that decision. Instead I made friends with the Afrikaaners and spent the days when not swimming attending their tea-parties with all the cream cakes they so adored.

I had encountered black people before Africa, but not in the same number. I was astonished to hear the local Afrikaans and other whites calling every black male “Boy” regardless of his age. It seemed odd and rude that a young white would address a black man twenty years his senior as “Boy”. And the women, they were called “Girl”, even the old ones.

There were surprising folk amongst the white settlers.

The dairy was located in the mountains behind town; our neighbour took me to show the way and introduced me to the woman, for I was expected to make the trip once a month to pay the dairy bill.

As we arrived I noticed all curtains were drawn. I felt nervous as Mavis knocked on the dairy-woman's door.

It opened, a face older than any I had ever seen peered out. She smiled when Mavis introduced me, a brief shifting of wrinkle lines. Parchment faced she invited us into her darkened interior. Mavis whispered explanation about how drawn curtains cool a room from furnace heat. The old woman called to her maid and a tray of coffee and rusks soon appeared.

I listened in horrified interest as by way of introduction she told of her daughter locked in the back room. “Frightened by a snake,” Mavis repeated to me.

The woman, heavy-pregnant with the child in her womb believed it affected the babe. “Quite mad,” said Mavis of the imprisoned girl. Now an adult, each day she received washing, dressing, hair-comb but no release.

And no one was allowed to see her.

“She is completely white,” said the old woman.

I shuddered. That poor girl! “Never to see the sunshine, feel the sea upon her skin?” I asked. “The wind through her hair?”

Each month I made the journey up into the hills to the dairy, and sat with the old lady and each month hoped for a glimpse of the strange white creature in the back room. Never saw her once.

The Penguin is My Baby

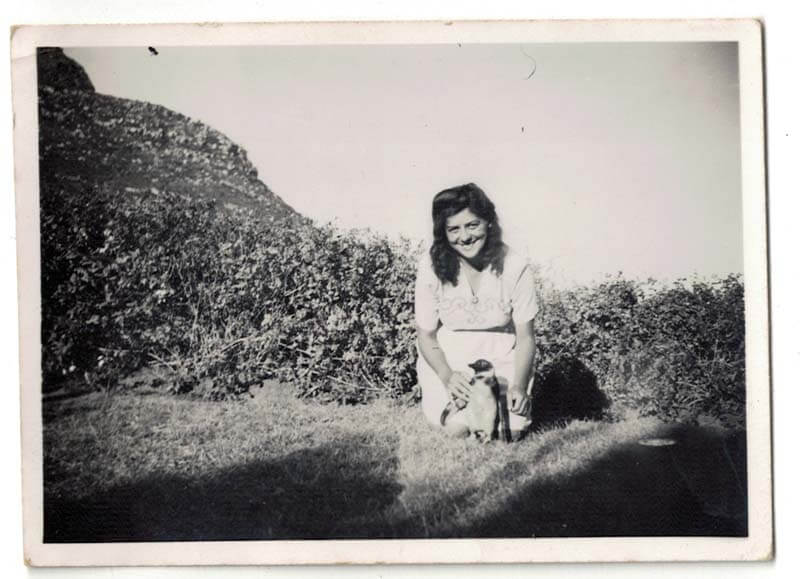

Returning from this odd experience, desperate to plunge into the cooling sea I found an injured penguin on the beach. Bird had head wounds, lots of blood. So I picked it up easily. It seemed dazed but let me carry him home in my arms. I assumed it was male, bathed its wounds, and applied ointment where needed.

Penguins, I soon discovered are not domestic animals. They smell very strong indeed. I put it in the kitchen but the stench was terrible and when Walter came home that night, trouble followed.

“That thing is not staying in the house!” he yelled.

There was an outside toilet. I shut him in, having made a little bed out of newspaper. Next morning when Walter was gone to work, opened the outhouse door to find, to my relief, the penguin still alive. It stood serene in the doorway looking up at me. Wasn't sure what it wanted so opened a tin of sardines, put them in a dish. Penguin looked, sniffed and turned away.

Tried him on sardine several times before I guessed the problem.

Found a jam jar, made a net from old curtains and cycled to a rock pool on the shore, to fish. Filled jar, later I cycled back and emptied them into a washing up bowl. Penguin sniffed and dived in, happily gorging fish in a bowl.

Free Peter Didn't Want to be Free

Every morning I made the trip to the rock pool before Walter woke. Made me laugh to share the house with two individuals whose lives revolved around fish.

When the wound healed I released the penguin into the sea. Took him with me for a swim. Happy he followed me in for some distance; and when I heaved out of the water, so did the bird. Sat with me while a dried myself and when I got onto my bicycle, he nuzzled close to my foot, stared up with that look of serene curiosity.

He wouldn't leave so I put him back in the basket and brought him home again.

Walter's annoyance came at full volume. He swore and carried on, alarmingly. “Stinking creature. Get it out!”

But I was by then quite attached to the bird, gave him name. Peter. Every day I put him in my basket and took him to the beach to swim. And every day he came home with me.

What happened to the penguin?

'Walter got a new job in the desert and we had to leave him behind.'

Thank you for your company on this introduction to Margo Williams' backstory. If you would like to know more about her investigations of the paranormal read this book. Now available from Amazon.